Susan sully sold her first book at age 8.

Her neighboring sidewalk vendor, a lemonade stand, did better.

“She made a lot more money than I did, and I should have paid attention!”

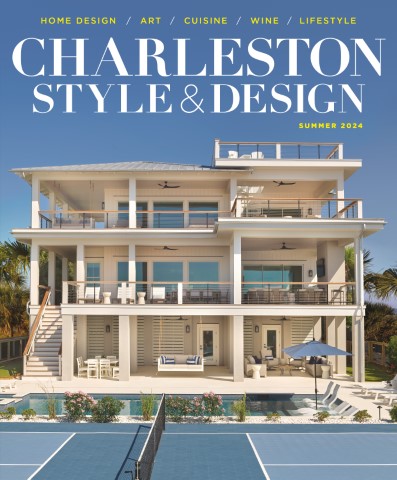

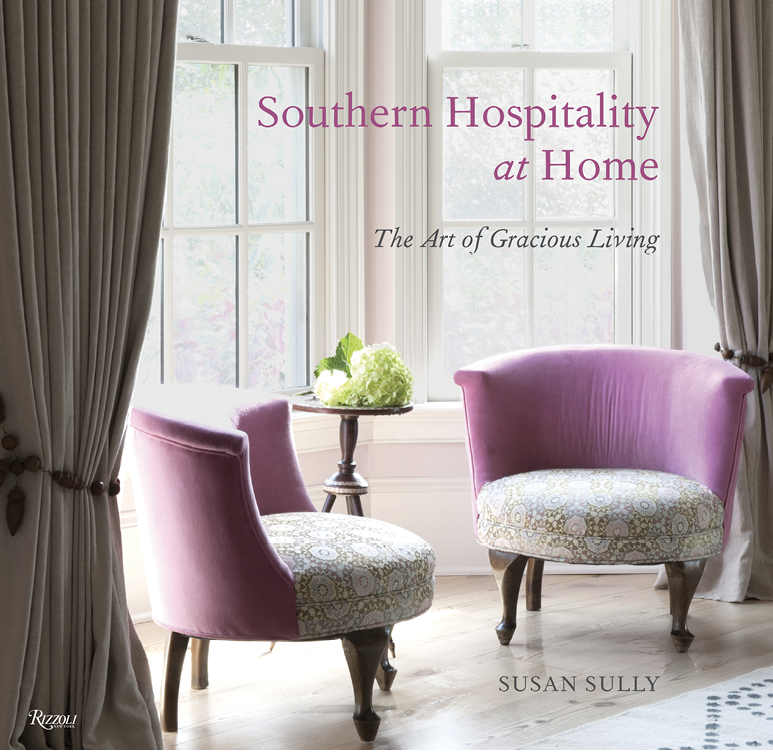

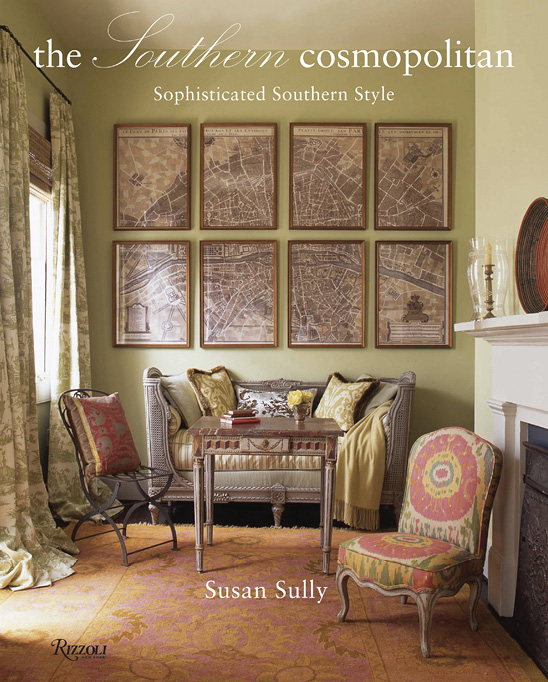

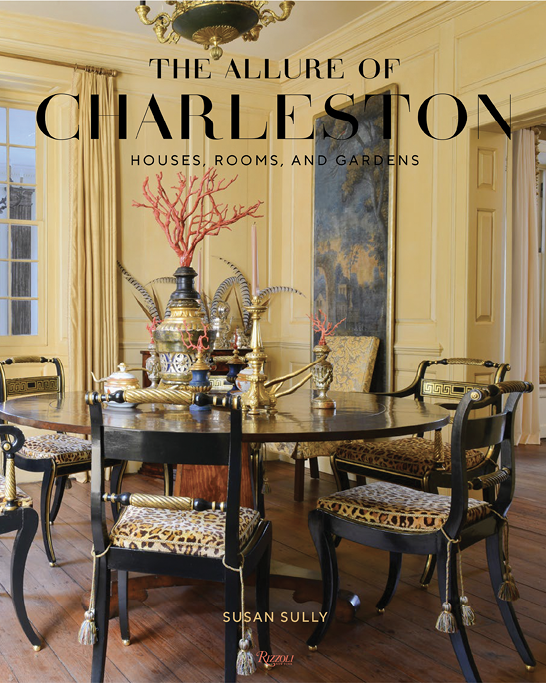

Happily, she didn’t. Charleston’s resident design maven hasn’t done too shabbily in the large-format publishing world. With 18 books on architecture and interiors to her credit, most recently The Allure of Charleston: Architecture, Rooms, and Gardens (Rizzoli International), Sully has helped define a philosophy of style.

Her other best-selling titles include Charleston Style, New Moroccan Style, The Southern Cosmopolitan, and Casa Florida. A familiar fixture on the lecture circuit, Sully also has collaborated on a number of books with leading American architecture and design firms, while contributing articles to The New York Times, Town & Country Travel, Veranda, and other publications.

Sully, a graduate of Yale University, is a former archives and public information officer at the Pace Gallery in New York and one-time director of development at the Poetry Society of America.

A self-described “homing pigeon,” Sully returned to Charleston in 2016 after stints in New Orleans and Asheville, North Carolina.

Currently, she is immersed in research for her first novel.

Q: How would you define your approach to architecture?

Sully: I don’t consider myself to be an architectural historian. I consider myself to be an architectural medium. Buildings talk, and I tell their story.

Q: Was it inevitable that you would write about architectural design?

Sully: Actually, I thought I wanted to write fiction, but I was intimidated by it. I came down here from New York with the intention of becoming a writer, though I didn’t know what I was going to write. But when I started walking down the streets of Charleston, the buildings began talking to me.

Q: Who or what have been your principal influences?

Sully: Professor Vincent Scully, one of the greatest architectural historians in America, whom I studied under at Yale. He gave me permission to experience architecture the way I experienced it. From a very emotive perspective. It was eye-opening. Two of the architects I’ve coauthored books with also studied under him.

Q: Have you developed a personal philosophy of design?

Sully: Yes. I was first exposed to architecture in a meaningful way in two places. In Milledgeville, Georgia, which is my mother’s hometown. I grew up in Connecticut and every time I went to Milledgeville it was this magical place to me. The architecture was associated with a whole way of life down there: the heat, the sitting on porches, the food, the telling of stories. It wasn’t just the architecture, it was the lives intertwined with the architecture. That was really important to what my philosophy is. The second one was when I was 7. My family took this long voyage through Italy, Greece, India and England. I discovered that architecture was fun, that it was engaging and exciting. I want to ignite that interest and excitement in other people and show the ways it can enrich your life.

Q: What of interiors and the integration of art and furnishings?

Sully: Rooms tell you so many stories. Interior and exterior architecture both intrigue me. And I do love the decorative arts. Objects fascinate me.

Q: What roles do color and texture play in your philosophy?

Sully: They communicate very directly to the senses. There is nothing filtering them. We see it; we feel it. Though it’s abstract and left to you to interpret it. It’s an expression of material history rather than an academic history of language and ideas. Material history is about an object that holds ideas.

Q: Are you drawn to harmony in design or unexpected, striking contrasts?

Sully: If the person feels their home is either a reflection of who they are or a place in which they find joy, that’s all that matters. When I walk into a room, I can tell whether or not it’s such a place. That’s where authenticity comes in. They know something about themselves, and they feel safe expressing it.

Q: Where do interior designers come in?

Sully: If you have a good one, they can work with the things that you have and love and create unity. Really skilled designers know how to layer a space so that it looks like it was put together over time. Personally, I’m looking for the most interesting homes, not the most beautiful.

Q: Large-format books can be a tough sell for publishers and buyers. How have you managed it?

Sully: I have been extraordinarily fortunate in that and in having a good track record. It’s helpful that my first Charleston book and my last Charleston book were my alpha and omega.

Q: Do you feel you are entering a new creative phase?

Sully: I’m at the age when somebody should do that. It’s not only my writing but my photography, which in the past has always been about documenting things in a way that was sensual and evocative. I’ve just gotten to the point where I want to photograph things that aren’t art related.

Q: What can you tell us about the novel at this stage?

Sully: I’m almost done with a kind of storyboard for it. I know most of what it will be, which is exciting. I just don’t know what the ending is yet. The working title is Reb, and it is loosely based on the life of my grandmother, who grew up on a small cotton plantation near Abbeville, South Carolina. She gave me these various objects, like a silver tea service, that are talismans to me. Each time I got an object I was told a story. And it is through these objects and their emotional provenance that the book is told. These objects serve as touchstones throughout the book. *

Bill Thompson covers the arts, books and design.